In the interview with Shawna Legarza published on Wildfire Today this morning, the National Fire Director for the U.S. Forest Service said in response to a question about how many large air tankers are required:

I would say we need anywhere from 18 to 28, you know that’s what it says in the [2012 Large Airtanker] Modernization Strategy. I think that’s a good range.

We re-read that Strategy, and could not find any independent conclusion reached by the authors about the number of air tankers. But, on page 3 there was this:

Continued work is ongoing to determine the optimum number of aircraft to meet the wildfire response need, but studies have shown that it is likely that between 18 and 28³ aircraft are needed.

The referred to footnote #3 is this:

³The requirements for large airtankers have been derived from the “National Interagency Aviation Council Phase III Report, December 7, 2007”, and the “Interagency National Study of Large Airtankers to Support Initial Attack and Large Fire Suppression, Phase 2, November 1996”.

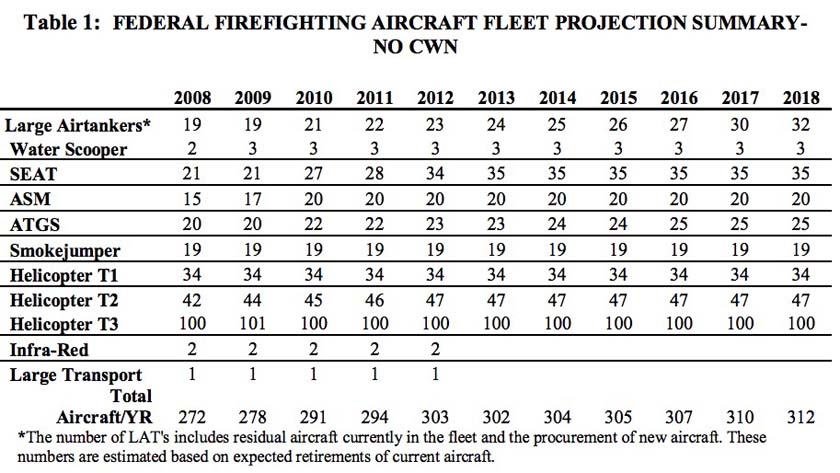

The first of the two studies recommended increasing the number of large air tankers on exclusive use contracts from 19 in 2008 to 32 in 2018. Plus, there would be three water scoopers by 2018, bringing the total up to 35. The table below is from the study.

The second document, the 21-year old study from 1996, recommended 20 P3-A aircraft, 10 C-130B aircraft, and 11 C-130E aircraft, for a total of 41 large air tankers.

The “18 to 28” air tankers mentioned in passing in the “2012 Large Airtanker Modernization Strategy” is not reflected in the referrals indicated in the footnote.

Much has changed in the world of aerial firefighting in the 10 to 21 years since those two studies were written. (They are two of the 16 air tanker studies and reports listed on the Wildfire Today Documents page.)

But what has not changed is that the numbers in these studies, written by smart, well-meaning people, are basically back of envelope stuff. There has not been in the United States a thorough, well designed analysis of the effectiveness of aerial attack, exactly how much retardant is needed in a certain time frame, where aircraft need to be based, and how many and what type of aircraft are required.

Under pressure from Congress and the GAO to justify the aerial firefighting program, in 2012 the U.S. Forest Service began a program to develop metrics and collect data to document and quantify the effectiveness of aircraft in assisting firefighters on the ground. This became the Aerial Firefighting Use and Effectiveness (AFUE) program. It will be several more years before they expect to release findings related to the effectiveness and probability of success of aerial resources.

We asked “Bean” Barrett, a frequent contributor on Fire Aviation, for his view on how many air tankers are needed. He started by saying the general theme of the letter written in 2012 by Ken Pimlott, the Director of CAL FIRE, to the Chief of the Forest Service, is still applicable today. Director Pimlott said in part that the then-recent USFS Large Air Tanker Modernization Strategy was insufficient to meet the needs of the combined federal, state and local wildland firefighting missions.

Bean’s further input is below.

****

“18-28 Large Air Tankers as the Federal inventory objective? Could we be a little more precise? What if the federal requirement was defined by referring to something like required retardant gallons delivered/ hour/ mile from base/ dollar. At least then, some basic economic analysis could be used to justify inventory when it comes around to contracts and budget time. What about required number of LAT sorties/ year / GACC?

“Do the NICC UTF numbers actually identify requirements shortfalls? How many IMT’s don’t bother to request air support when they don’t think any air is available? UTF data would be very useful to demonstrate inventory shortfall if UTF’s represented all the unfilled need. In 2015 UTF’s represented a 10% shortfall in LAT sortie generation requirements. In 2016 UTF’s represented a 15% shortfall. Based on what I would say are very conservative UTF numbers, there has been at least a 10-15% shortfall in available LAT inventory over the last two years.

“Really hard to comment on inventory objectives when it isn’t clear what the Large Air Tanker mission is. To paraphrase Lewis Carroll, if you don’t know what you want to do with them, any number will be enough.

“Is the mission IA or extended attack? Is it ground support or independent tasking? What effects are trying to be achieved and how well are they achieved? Should an attack within 24 hours really be considered IA for an aircraft? CALFIRE wants aircraft on scene in 20 minutes. The Australians want <30 minutes.

“Just for openers, this is a very good ops analysis piece using real data from real fires: https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs_journals/2016/rmrs_2016_stonesifer_c001.pdf

Our results confirm earlier research results related to LAT use and challenge a long-held assumption that LATs are applied primarily to assist in the building of line to contain fires during IA.

Perhaps most importantly, we highlight system-wide deficiencies in data collection related to objectives, conditions of use and outcomes for LAT use.

Our current inability to capture drop objectives and link specific actions to subsequent outcomes precludes our ability to draw any conclusion about the effectiveness of the federal LAT programme.

“A finding in the study … Mean time of day for drops was 15:39 and only about half of the drops were IA. This makes it really difficult to say that LAT’s are there to support the ground crews.

“Why not tie LAT requirements directly to the number and type of IMT’s mobilized? Perhaps some ops analysis would find a ratio of number and type of tankers to type of IMT’s mobilized? Or perhaps a ratio of days IMT’s mobilized to LAT sorties required for support? Start thinking like an integrated air-ground team and define air requirements in terms of IMT’s or crews mobilized and supported. When the definition of Head Quarters units [ IMT’s] composition or types of ground crews includes the number and type of aircraft included in support, the inventory objective for tankers will fix itself. I expect everyone has a much better handle on the amount and type of ground support required today compared to the very vague understanding of tanker requirements. Tie air requirements to the better understood ground requirements.

“Once the real data gets collected and analyzed, it may be found that the best air IA assets for type 3 IMT’s aren’t fixed wing tankers. (Provided IA is redefined to something like arrival within 20-30 minutes of dispatch.)”

Wow, I hope Ms. Legarza and Mr. Dunton don’t feel that way, too many fixed wing air tankers. As Mr. Watt stated the need for gallons delivered within the first burning period 15,000 to 30,000 gallons of long term retardant is a valid statement. The Federal air tanker program and Federal tanker bases in California has been “gutted.” No such thing as Federal air tanker I.A. in California. A few exception San Bernardino, Lancaster, Ramona is trying to go Fed again. (unless on days off) big media and political areas. No wonder Congress and the GOA are confused on what to fund. Too many studies, too little I.A. experience at the Fed top and a position of management only, not immediate suppression. “aircraft on order” is a death sentence for initial attack. I would hope that the people (AFUE) running around the country looking at retardant on the ground would investigate what if retardant was delivered within the first 20 to 30 minutes? What probability of containment might have occurred.

If I may: The general consensus of ANY of your readers – who are employed because they have a stake in the aerial firefighting industrial complex – will always be that there are not enough air tankers, helicopters, scoopers, lead planes, air attack. etc.

The only people who will say we have too many are Shawna Legarza and Ron Dunton…and congress.

If you think that we need more airtankers – call your FMO or your congressman.

By the way, Can you imagine the alternative to having the FS contract studies? Themselves performing their own research… on themselves? I think it is money well spent. If you have a contractor provide you an estimate on a home improvement project, are you obligated to have hime or her perform the work? The FS is not obligated to follow the research they asked for.

If you think that continually researching the topic is expensive, I beg a cpomparison: Ask one of the airtanker drivers who troll these pages like vultures, how much money their company made last summer from the Forest Service.

Nine Canadian provinces and territories operate sizeable fleets of large air tanker and/or scoopers, and collect a lot of data. No Canadian fire fighting agency contracts large Type 1 helicopters with buckets or tanks on a proactive basis.

There was a very significant piece of research published by the RAND corporation in 2012 titled “Air Attack Against Wildfires – Understanding U.S. Forest Service Requirements for Large Aircraft”. This research was sponsored by the USFS and the USDA. The research is much more than back of the envelope. Why does this significant piece of research not get much attention?

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG1234.html

There is some interesting analysis in the Rand study. When many people think of that report, what they remember is that the U.S. Forest Service refused to release the document they paid $840,000 for, even after Wildfire Today filed a Freedom of Information Act Request. Finally Rand released it. I don’t know if the Forest Service ever did.

One of the Forest Service’s stated reasons for keeping the report secret was that “The data, analysis, and conclusion in this report are not accurate or complete” and that the USFS wanted “to protect against public confusion that might result from premature disclosure.”

This was, in my opinion, a flagrant abuse of the FOIA system. They knew that Wildfire Today did not have the financial resources to hire attorneys to fight their ridiculous decision in court.

People also may remember that the USFS instructed Rand to not consider the use of very large air tankers, such as the DC-10 and 747 that carry 12,000 to 20,000 gallons, so they only studied the use of 3,000-gallon tankers, 2,700-gallon helicopters, and 1,600-gallon scoopers. No SEATS.

And, Rand’s conclusion was, there should be more scoopers than large air tankers. In one scenario they analyzed a mix of 48 scoopers and only 8 large air tankers. Their final suggestion was “15 to 30 scoopers to be used in conjunction with two to six air tankers and a comparable number of 2,700-gallon helicopters”.

After receiving the report, but before it was released, the USFS gave the company a non-competitive contract for another air tanker study, but it was cancelled after protests from other potential vendors.

In the good old days at Redding Air Attack Base there were four airtankers assigned, two state and two fed. Normally, only one fed tanker was moved out of the area though both could be committed elsewhere. Medford, K-Falls, Chester, Stead and sometimes Chico had federal assets. Between all resources it wasn’t uncommon to have 6-10 tankers working an emerging fire. The desired outcome and attack mode dictate the flow rate. I found that 15,000 to 30,000 gallons of retardant was needed in the first burning period to knock a fire down for the crews to contain overnight.

California/Region 5 nominally had 21-23 state tankers and up to 15 fed tankers on multi-base contracts. Adding the boundary bases in adjacent Regions added four of five more. The definition of initial attack drives the flow rate required. California state policy is twenty minutes. It an agency is willing to plan on longer IA arrival times then fewer assets can be justified. The problem is the emerging/extended attack fire that threatens to become a major incident. If you can’t pull additional resources to increase the retardant flow rate to match the fire then you help create the next big fire.

Somewhere the concept of containment in the first burning period took a big hit from planners. The money spent on an aggressive air attack that is successful saves much more money than the support costs on major fires.

There it is there by Mr. Watt, well stated! Every minute counts during the I.A. period, like the golden hour. I have a better approach to being Forest Service “cheap” on fixed wing air tankers. If a fire escapes the second burning period, everyone goes home. LET HER RIP. The fire will eventually seek it own containment parameters like in the “before man” period. Isn’t that what usually happens today anyway? Maybe people will work on their defensible space if that was the policy, NOT.