Updated at 4:54 p.m. MST Nov. 17, 2021

Wednesday afternoon CO Fire Aviation released a statement that identified the pilot who was killed Nov. 16 during a night-flying air tanker mission on the Kruger Rock Fire southeast of Estes Park, Colorado.

The CO Fire Aviation family is deeply saddened by the sudden, tragic loss of one of our brothers serving as a tanker pilot. Marc Thor Olson was a highly decorated veteran of both the Army and Air Force with 32 years of service to our country. During Thor’s 42 years of flight, he had amassed more than 8,000 total flight hours with an impressive 1,000 hours of NVG flight including in combat and civilian flight.

Co Fire maintains a close working relationship with multi regulatory agencies and is fully cooperating with the proper authorities and partners during this investigation.

While we are gravely aware of the inherent dangers of aerial fire fighting and the questions that remain; we ask that family and friends be given distance and time to process and heal as we grieve this loss. Your prayers are appreciated during this difficult time.

A preliminary map appears to show that the fire was just inside the boundary of the Roosevelt National Forest. The Larimer County Sheriff’s office said on Wednesday that as of 7 a.m. Wednesday the fire was managed by a unified command with the US Forest Service and the Sheriff. In Colorado the local county sheriffs are given the responsibility for suppressing wildfires outside of cities unless they are on federal land.

The crash occurred at about 6:35 p.m MST on Tuesday Nov. 16 while attempting to suppress the fire. This was about 1 hour and 49 minutes after sunset, and was the first time a fixed wing air tanker had dropped fire suppressant on a fire at night in Colorado.

11:17 p.m. MST Nov. 16, 2021

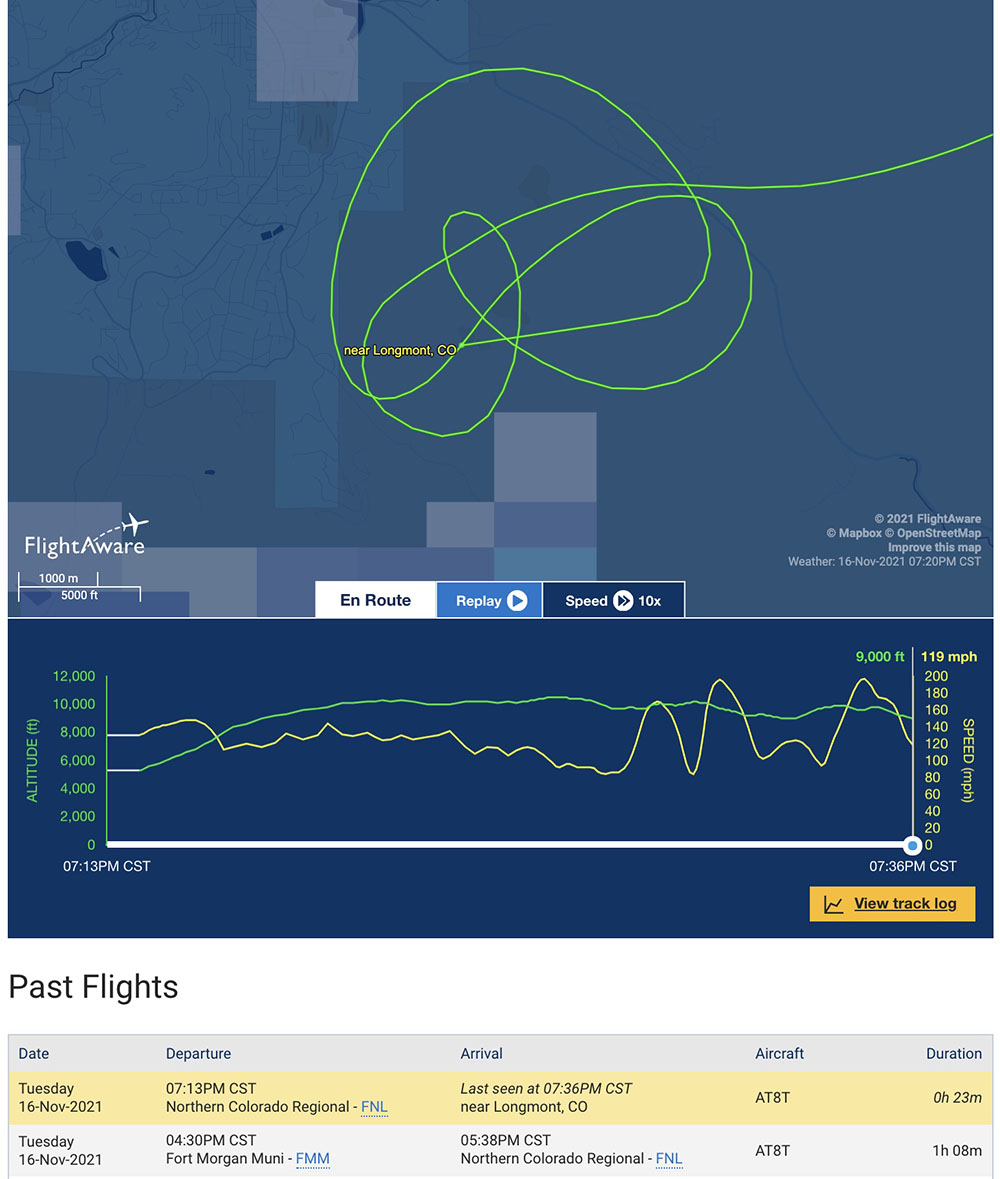

An air tanker that was working the Kruger Rock Fire southeast of Estes Park, Colorado Tuesday night November 16 crashed, killing the pilot, the only person on board. The Single Engine Air Tanker (SEAT) had taken off from Northern Colorado Regional Airport, formerly known as the Fort Collins-Loveland Municipal Airport, at 6:13 p.m. MST Nov. 16 and disappeared from flight tracking 22 minutes later at 6:35 p.m. MST. Earlier in the day it departed from the Fort Morgan, Colorado airport, orbited the fire about half a dozen times, then landed at Northern Colorado Regional Airport at 4:38 p.m. MST.

The incident was first reported by KUSA, 9News in Denver. Marc Sallinger, reporter for the station, had interviewed the pilot earlier in the day, and wrote on Twitter, “My thoughts and prayers are with the pilot who took off tonight, so excited for this history-making flight. He told me ‘this is the culmination of 5 years of hard work.’ He showed me his night vision goggles and how they worked. He was so kind. Holding out hope for him.”

Eyewitnesses reported the crash at approximately 6:37 p.m., but in the dark it was very difficult to pinpoint the location. After three hours of searching, firefighters found it near the south end of Hermit Park. Unfortunately the pilot was deceased.

The aircraft was an Air Tractor 802A, registration number N802NZ, owned by CO Fire Aviation. In 2018 we wrote about the company’s efforts to configure this aircraft for fighting fires at night. Helicopters have been doing it off and on for decades, but a fixed wing air tanker dropping retardant on a fire at night is extremely rare. In 2020 and 2021 CO Fire Aviation had one of their SEATs working on a night-flying contract in Oregon. The company says they are the only operators of night-flying fixed wing air tankers.

Earlier this year a video was posted on YouTube that featured CO Fire Aviation conducting a night-flying demonstration at Loveland, Colorado. That segment begins at 8:15 in the video.

BREAKING: We’re hearing reports this plane has crashed while fighting the wildfire in Estes Park

It was the first time a fixed-wing aircraft had ever fought a fire at night using night vision here in CO

Company that owns is racing to Estes and trying to learn more #9News pic.twitter.com/izpgNchMYK

— Marc Sallinger (@MarcSallinger) November 17, 2021

For the first time ever, firefighters will use a fixed-wing aircraft to fight a fire at night when a plane takes off soon loaded with fire suppressant. This has never been done before. It’ll fly all night to fight the wildfire in Estes Park #9News pic.twitter.com/K5ds8Pl22x

— Marc Sallinger (@MarcSallinger) November 17, 2021

At 6 p.m. the Larimer County Sheriff’s office said the Kruger Rock Fire had burned about 133 acres. More information about the fire is on Wildfire Today.

Our sincere condolences go out to the pilot’s family, friends, and coworkers.

The article was edited to show that the crash was first reported by KUSA, 9News in Denver.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Tom.

Lakeview, John Day, etc? Were there “training lanes” that were considered successful?

Some of those locations are mixed with some mountains but not like the Estes park areas.

Probably a “little” safer in those High Desert locations to accomplish in some areas without a lot of chatter about powerlines.

Otherwise, I am sure Marc Olson flew these in those locations and that the Estes Park areas were different in topography and late fall flying conditions (CAT- Clear Air Turbulence) were some POSSIBLE factors that were somewhat different in Oregon

The wreckage is still warm. Now is not the time to assign blame, or make assumptions.

The pilot of the aircraft made statements earlier in the day that he was excited about the technology and the use. He had significant NVG experience. He wasn’t a new pilot.

There is plenty of time to discuss the limitations of single engine aircraft, night flight, mountain flight, wind and weather over the fire, etc.

Single engine flight over mountainous terrain poses the obvious challenge of where to put the airplane if sustained flight becomes no longer an option; the choices are reduced by the terrain. Options are reduced by smoke, weather, wind, and of course, daylight. Mitigating that is night vision. Night vision comes with particular limitations, the most notable of which is that one isn’t actually looking out of the aircraft. One is wearing blinders, inside of which are projected an image that lacks depth perception, portraying what the night vision equipment assembles as a picture of the world. It’s an important limitation: one isn’t seeing the world outside. One is looking at a little screen an inch and a half from one’s eyes, and the distinction between the two is critical.

The pilot understood this distinction, as well as his assignment.

In the tanker world, we live in a can-do business. Can you put that retardant over there? Yes, I can. Or, no, but I can do this. We’re all about can-do. Coupled with can-do must be a willingness to say, “no.”

This mishap is unique. Most every loss we experience has remarkably common elements; the same things keep costing us our lives; most occur at roughly the same time of day; eerily similar fire weather conditions, and so on. In fact, in broader terms, almost every fatality that occurs on a fire happens under remarkably similar circumstances. This event, this loss, does share commonality. Higher winds, terrain. Possibly fatigue. But the night element and the use of night vision equipment will bear scrutiny.

At this stage, we don’t know what happened. It’s inappropriate to speculate, and disrespectful of the dead, particularly to start laying blame in absence of fact. If an engine failure occurred, the issue of night vision equipment might, or might not be relevant. If a medical issue occurred, many other issues may not be relevant. What is important is that this pilot knew the risks, knew the costs, and knew his expectations, and he felt strongly enough about it that he was willing to bet his life on the outcome, as we all do, every time we launch on a fire, based on the circumstances before us. Until the facts are in, it may be best to respect his decision and the cost, and wait until the circumstances of this event are known.

No disrespect to the accident pilot, his family, or the company he worked for but – this mishap is not unique…it’s consistent with an evaluation of risk that some (not all) pilots, aircraft companies, and government personnel either ignore or have a hard time conceptualizing.

Hi Steve,

That’s quite a statement, please elaborate.

Our thoughts & prayers to his family & friends from the Florida Forest Service

My heart, thoughts, and prayers are with

The pilot’s family, co-workers and friends. It just totally break my heart to read this.

Bill, actually is was KUSA, 9News in Denver that first reported it, and Sallinger reports for them.

Thank you. Fixed it.

So, what was one SEAT going to accomplish that couldn’t wait for daybreak? What a sad situation. RIP.

Sad to read this for comrades and family, but know the efforts are not in vain. Much to learn in night ops in mtn terrain without spotter-chopper (plane-guard). Lucky us 0130 Jan 1963 ditch–Sea of Japan bolter off Yorktown (CVS-10)–1st 3-man night helo rescue.

So much too learn indeed; most importantly don’t fly airtankers at night, for many reasons. This accident is the result of little or no where-with-all about risk management…idiotic at best.

Actually to be honest I live in oregon and have been working with tanker 860 the last 3 years and night seat operations have been practiced here and in practice they were successful so where none of us where actually in the plane with the pilot we do not know what happened. Thank you for your time

Successful? I don’t believe it.

The Sheriffs hubris is responsible for this, he should stick to LE and let the pros handle aerial firefighting. RIP and fair winds Aviator.