Down below we have republished, with permission, an article about firefighting helicopters in San Diego County written two years after the huge and disastrous 2003 Cedar Fire. But first, a little history about the initial attack on that fire.

When I think of the Cedar Fire in San Diego County, three things come mind.

- One: It was huge, 273,246 acres, at the time the largest in the recorded history of California.

- Two: 14 people were killed including one firefighter.

- Three: individuals from the County Sheriff’s office complained bitterly, publicly, and often that they were not allowed by the U.S. Forest Service to use a helicopter to drop water on it, implying they could have stopped the fire in the first hour or two.

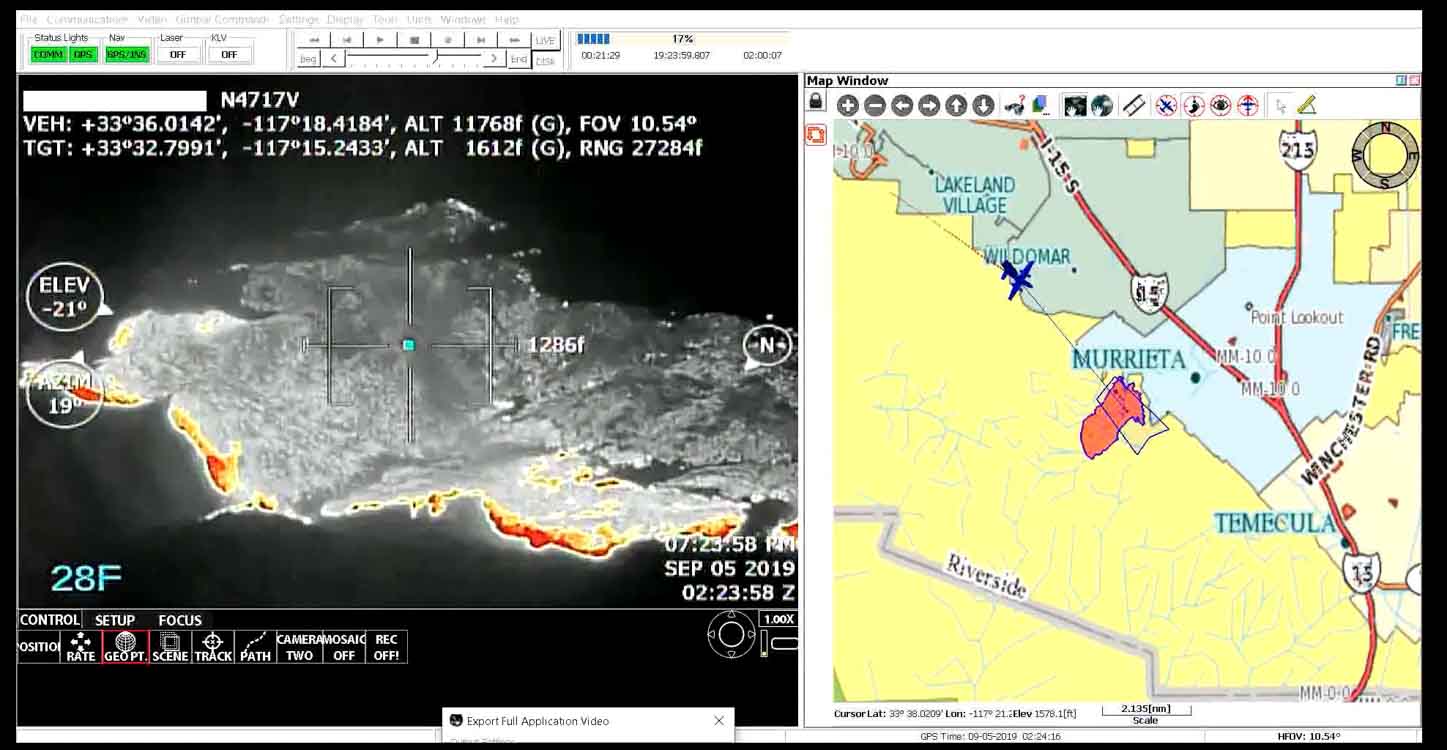

Two thoughts about the last item. The use of the helicopter was denied because it was too close to flight cutoff time, 30 minutes after sunset, which was at 6:05 p.m. on October 25, 2003. The other factor was the Santa Ana winds which were screaming that night. The fire was reported at 5:41 p.m. and by 3 a.m. the size was estimated at 62,000 acres. Under those extreme conditions any aircraft, fixed or rotor wing, would have been totally ineffective.

From the LA Times, October 31, 2003:

The Forest Service “insisted that [the sheriff’s helicopter] not respond with the Bambi bucket due to rules, regulations on water drops after the cutoff hour,” according to a 6:17 p.m. sheriff’s dispatch entry.

“We found out a long time ago that helicopters with little buckets are not effective in fighting brush fires like this,” said Rich Hawkins, [Cleveland National Forest] fire chief with the U.S. Forest Service. “No little helicopter with its little bucket would have done much good.”

Here is the story from the San Diego Reader published March 24, 2005:

By Joe Deegan

The value of helicopters in fighting fires is “the quick attack,” says Brian Fennessy, manager of San Diego’s Regional Fire and Rescue Helicopter Program. “If you can get a load of water and a crew in there to hit early, you have a chance of stopping fires before they become large.”

Three days before the late-October 2003 Cedar Fire, the San Diego Fire-Rescue Department’s helicopter left the county. A 120-day lease with Boise, Idaho’s Kachina-Helijet Aviation had run out. During its stay here, no major fires gave the chopper an opportunity to show what it could do.

The initial absence of the helicopter was only one of many resource shortfalls that firefighters faced throughout the Cedar Fire. An urge to blame government began immediately afterward. But within a week, on November 1, the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Kelly Thornton and Luis Monteagudo, Jr. wrote that some local officials claimed “taxpayers should look in the mirror.” And the reporters quoted San Diego fire chief Jeff Bowman as saying, “The city didn’t have enough resources because people aren’t willing to pay for them.” As though to back up the chief’s view, Thornton and Monteagudo wrote, “Dozens of ballot measures to raise taxes for fire protection have failed over the past three decades.”

It didn’t take long for San Diego to retrieve its helicopter. In fact, the aircraft never made it out of the state. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Prevention commandeered it to help fight a huge fire in the San Bernardino Mountains that had already been raging for several days at the time the Cedar Fire broke out.

The Cedar Fire started on a Saturday night. “Already I had gone up to the San Bernardino fire as a member of the management team,” says Fennessy, who mentions several local firefighters who went with him. “Then we got a call from our fire chief on Sunday morning. He’d been in contact with the mayor and councilmembers who wanted to know what it would take to get the helicopter again. They wanted it back on contract. It took me until Monday to get it because people also were losing homes up there. So the state commander didn’t want to let anything go.”

But Kachina-Helijet came up with another chopper from Boise for the San Bernardino fire, according to Fennessy. “That allowed me and the pilot to bring our helicopter back down,” he says. “It was here and ready to go by 10:30 Monday morning.” The city has had the aircraft ever since.

“To be honest, though,” says Fire-Rescue Department spokesman Maurice Luque, “this and ten other helicopters like it wouldn’t have made much difference after the Cedar Fire was going. The weather was the key factor.” Fennessy agrees but adds, “We’d have had some victories along the way; we’d have saved some homes. This helicopter and others were saving homes in the [San Bernardino] fire. They still lost lots of homes up there but not as many as they might have without helicopters.”

I ask Fennessy, did the city end its initial four-month use of the helicopter before the Cedar Fire because the program was only experimental?

“No, officials did acknowledge that it was a need,” he answers, “but it came down to dollars and cents. The city, county, and state are suffering difficult fiscal times, and there are a lot of competing priorities in San Diego.”

Shortly after the Cedar Fire, the board of supervisors decided that San Diego County ought to have a helicopter. So, the city’s Fire-Rescue Department leased a second one from Kachina, which the county pays for. Now, Copter One and Copter Two and their four-man crews comprise the San Diego Regional Fire and Rescue Helicopter Program. The city keeps Copter One (a twin-engine Bell 212 manufactured by Bell Textron in Texas) at Montgomery Field. Fallbrook is the home of the county’s Bell 214 Copter Two, an older single-engine product of Bell Textron.

I flinch at the $256,000 monthly lease on each machine. “Besides the helicopter,” says Fennessy, “Kachina provides its pilot, the fuel it uses, a fuel truck with driver, and maintenance.” To keep the pilots, all out-of-towners, near enough for emergency calls, Kachina puts them up in nearby motels during their 12-day rotations in San Diego. The company has similar contracts with the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and other organizations throughout the western United States, especially during fire seasons.

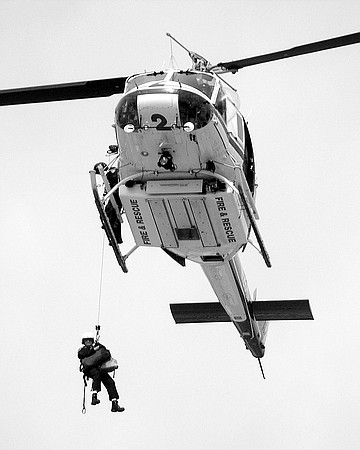

Luque is anxious to point out that “fighting fires is only one part of the helicopters’ total capability. To have one sitting here only to be used for fires wouldn’t be cost effective,” he says. “That’s why we use it for rescue and transport, too.”

I am standing before Copter One at Montgomery Field. Fennessy shows me a mechanism inside the helicopter that can swivel out and drop 250 feet of one-eighth-inch cable from its doors. The cable can hold up to 600 pounds, enough to lift two people. “There is not a spot in the county that we can’t reach to rescue someone with a broken leg or having a heart attack.” Mercy Air is San Diego County’s only licensed air-ambulance medical provider, according to Fennessy. “But we are the county’s ‘advanced life-support rescue’ operation. In case Mercy’s estimated time of arrival is too long, we are called to medical emergencies requiring the fastest transport. We have onboard defibrillators and all the drugs; everything that’s in an ambulance.”

The crews of the helicopters consist of Kachina’s pilot, a San Diego Fire-Rescue Department captain serving as crew chief, and two firefighter/paramedics. The fire captains’ pay is $37.47 per hour or $39.31 per hour for a 40-hour week. There are four levels of pay for San Diego firefighter-paramedics, from $17.92 to $29. But the firefighters are not always city employees.

Eleven other agencies in San Diego County pay for firefighter/paramedics to staff the helicopters. Today, Dennis Robinson of the Oceanside Fire Department and William Pidgeon of the Barona Fire Department are scheduled to receive training aboard Copter One. The Regional Helicopter Program operates regularly for 16 hours each day. Copter One is available from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. and Copter Two from 11:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. “That way,” according to Fennessy, “two helicopters are in service during the hottest part of the day, the time most vulnerable to fires.” And the choppers substitute for each other when one of them is down. During off-hours, the program scrambles crews whenever an emergency demands it. Personnel can be assembled and ready to fly within an hour of a call, Fennessy says. When they are on duty but not responding to a call, they spend their time in training, both on the ground and in the air.

Because the crews work 84 hours every two weeks, their San Diego personnel receive 4 hours of overtime every pay period. Whenever emergency responses require more staffing, the fire department also pays overtime wages to personnel who have volunteered to be on a “will-work” list. With the city’s current finances in disarray, overtime wages for fire captains has recently become a hot-button issue. On March 8, Kenny Anderson reported on KPBS radio that last year, two fire-department employees made more money than the city’s police chief, fire chief, mayor, and city manager. One of them, he said, earned a base salary last year of $118,000 and overtime pay of $123,000 for a total of $241,000. The other made $212,000 in salary and overtime combined.

Luque tells me that Jeff Bowman decided early in his tenure as San Diego’s fire chief that paying overtime was more cost-effective than hiring new full-timers who require benefits. “A lot of times, those employees would only be sitting around doing nothing,” Luque says. But overtime hours are expensive in two ways: San Diego compensates them at a time-and-a-half rate, and they expand an employee’s pension benefits.

Critics are unanimous that the city’s pension system is the biggest culprit in San Diego’s current financial woes. In a February 18 editorial titled “Share the Burden,” the San Diego Union-Tribune called for San Diego City Firefighters and other unions to give up some of the pension benefits they have negotiated in the past several years. On Thursday, March 3, and Wednesday, March 9, I called firefighters governmental affairs representative Johnnie Perkins for comment. Twice Perkins did not answer his phone after his secretary took my name, so I left a message asking how much firefighters’ overtime pay affects their city pensions. As of press time, Perkins had not returned my call.

Epilog-

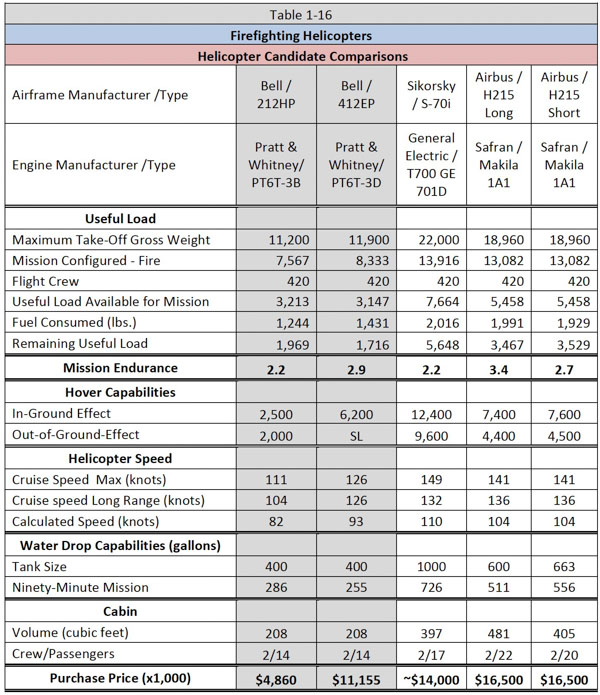

Today, San Diego Fire-Rescue has at least three firefighting helicopters, a Bell 212 (N800DM) and a Bell 412EP (N807JS) manufactured in 1980 and 2008, respectively, and a brand new Firehawk, a Sikorsky S-70i. San Diego County often has a cooperative deal with SDG&E which makes an Erickson Air-Crane available to assist firefighters.

Brian Fennessy worked his way up to become Chief of the San Diego Fire Department, and then in 2018 became Chief of the Orange County Fire Authority where he is working to upgrade their helicopter fleet. He is also Chair of the FIRESCOPE Board of Directors.