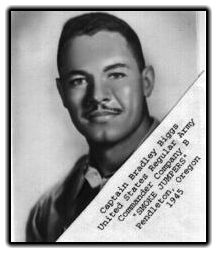

This article was written by retired Lt. Col. Bradley Biggs who was the first officer in America’s first all-black paratroop unit called the Triple Nickles, the 555th Battalion of the 82d Airborne. In 1943 the troop was created and trained to go to war, but instead was sent to the West Coast to fight forest fires started by Japanese balloon bombs. They were some of the early parachuters to fight fires, being formed a few years after the first fire jumps by two U.S. Forest Service employees in 1940. Later they became the first army unit to be integrated into the regular army during World War II.

This article is used with permission from TripleNickle.com.

By Bradley Biggs, Lt. Col. USA (Ret.)

Let us travel back to the origins of this unit, its conversion from a highly trained and combat ready parachute unit to the extremely dangerous role of “smoke jumping” and their performance in one of the best kept secret operations in World War II.

Through December 1944 and January 1945, the Triple Nickles had continued to jump, maneuver, and grow to a strength of over four hundred battle-ready officers and men. During that same period a far more deadly action was taking place on the battlefields of Belgium – the Battle of the Bulge – the massive German counter-attack in the Ardennes that began on 16 December 1944. It lasted more than a month and before the Germans were turned around, the American army had suffered some 77,000 casualties. Many of them had been paratroopers – men from General Jim Gavin’s 82nd Airborne Division and General Maxwell Taylor’s 101st who had made the heroic stand at Bastogne. The cry was out for replacements, not only in paratroopers ranks but throughout the European Theater of Operation (ETO) combat command.

At last we thought we were going to tangle with Hitler, whose embarrassment at the 1936 Olympics of a Black American named Jesse Owens was fresh in our minds. We eagerly anticipated pitting the Nazis against another group of black champions – men like Walter Morris, “Tiger Ted” Lowry, Jab Allen, Edwin Wills, Jim Bridges, Roger Walden, the list goes on.” Biggs recalls in his book THE TRIPLE NICKLES. He goes on to say that:

“We soon found that we would not go as a battalion but rather as a “reinforced company”. The reason was simple, we had not trained or maneuvered as a battalion. The original orders authorizing the 555th said we would not begin such training until we had reached a strength of twenty-nine officers and six hundred enlisted men. This could have been achieved if commanders army-wide had released volunteers and approved scores of requests for parachute duty.”

Eventually, the Triple Nickles would grow to more than 1,300 for duty, 600 in jump training at Fort Benning and 1,900 on the morning report rosters. But for now the smaller number had some advantages. It had enabled them to concentrate on intensive individual and small-unit training. Riflemen, machine gunners and mortar men had sharpened their aim to perfection. Training in judo and other forms of hand-to-hand combat were intensified. They had time and opportunity to become superb combat men. No goof-offs were allowed.

Moreover, men could be sent to schools for special training as riggers, jumpmasters, pathfinders, demolition experts, and communications men. Jump demonstrations and small unit maneuvers had helped them to perfect the tactics and logistics essential to many paratrooper combat missions, especially those requiring no more than a company-size force, such as an attack on an enemy communications center, bridge, enemy headquarters or road junction.

So when the order came to “skeletonize” to one reinforced company of eight officers and 160 men, the battalion had a pool of the best from which to choose the super-best. It began with a downward shift of command, a move for which everyone was fully prepared. The battalion executive officer, for example Captain Richard W. Williams became the company commander. Williams, the eleventh officer to join the Triple Nickles, had come to the organization as a first lieutenant from the 92nd Infantry Division. A well-built, muscular man, he was known as a tough, aggressive officer, filled with imaginative ideas and a sense of adventure.

So when the order came to “skeletonize” to one reinforced company of eight officers and 160 men, the battalion had a pool of the best from which to choose the super-best. It began with a downward shift of command, a move for which everyone was fully prepared. The battalion executive officer, for example Captain Richard W. Williams became the company commander. Williams, the eleventh officer to join the Triple Nickles, had come to the organization as a first lieutenant from the 92nd Infantry Division. A well-built, muscular man, he was known as a tough, aggressive officer, filled with imaginative ideas and a sense of adventure.

The battalion S3 (Plans and Training), lst Lt. Edwin Wills, the real “brains” of the training program, became the company executive officer. The commanders of A, B, and C rifle companies became platoon leaders, with each given his choice of an assistant platoon leader. Each former company commander chose his executive officer. First sergeants became platoon sergeants and platoon sergeants became squad leaders.

This special company was ready to take on anybody. But suddenly midway through the rigorous combat training, their destiny changed. By, April 1945, the German armies were collapsing. Americans were on the Elbe River – and would stay there. From the east the Russians were moving on Berlin, and the fall of the German capital was only weeks away. It seemed unlikely that any more paratroopers would be needed.

In late April 1945, the battalion received new orders – a “permanent change of station” to Pendleton Air Base, Pendleton, Oregon for duty with the U.S. Ninth Service Command on a ‘highly classified” mission in the U.S. Northwest. No one had any idea of what the mission would be.

Continue reading “Triple Nickles, paratroopers who fought wildfires during World War II”